1

I was starting to think we might be lost. Naturally nobody in our party would admit it. As long as a caver knows either where she is, where she’s coming from or where she’s going, she isn’t lost. If at least one of those conditions applies, the accepted term is ‘momentarily confused’. Trouble was, we had been momentarily confused for more than an hour by my reckoning, which is edging out of the territory of momentary confusion and reaching into the regions of confused until further notice.

Of course, since Gareth knew the cave intimately, he had not brought along a copy of the survey. I knew this because I had asked if he had one about seven junctions ago, and he had just snorted at me. He wasn’t worried about confusion, momentary or otherwise. Maybe something like it was a concern for lesser beings, but not him. He would keep going in the narrow twisting passage, stopping at crossroads to carefully examine our options, his ultra-powered helmet light that probably cost about as much as my car almost melting the pale grey mud off the rock walls. That head torch was designed for huge chambers, vast underground halls the size of aircraft hangars, not for tiny, muddy, single-file-only meanders which could have been just as comprehensively lit up with the cheapo Tesco helmet light special I was wearing. Maybe with my light you couldn’t make the mud shine as brightly, but anyway no sane person should be concerned about brightly shining mud at any point in her life.

Admittedly we were in unknown territory, or unknown to the five of us at least. We had understood as much when planning the trip last night. No one in our party had ever been to the far northern reaches of Ogof y Dwyn Gwaedlyd, mainly because the general belief was that there was nothing worth doing here. Somewhere beyond the jumble of small muddy passages there was supposed to be a chamber called White Room with some pretty nice cave formations, but our trip leader was Gareth, and he didn’t really give a fart about those. He styled himself an explorer, an adventurer, and as far as he was concerned, the only way a speleothem could capture his interest was if it was absolutely unique or big enough to actually use for something physical. I bet even he would like stals if they were big enough to climb. Few were.

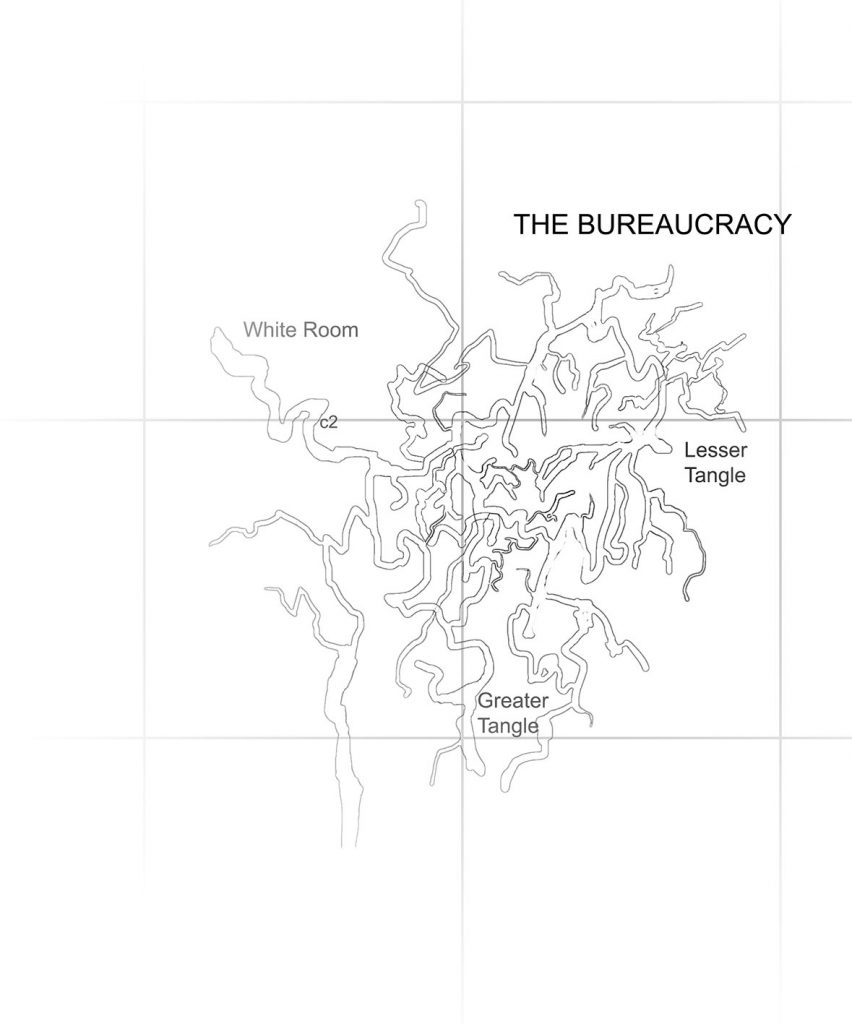

A few days back Gareth had heard a rumour. Somebody had found something in the far north of Dwyn Gwaedlyd. Problem was, nobody was actually talking any specifics. A caver at the pub had overheard a mention about a great new discovery, but not what exactly had been found, or indeed even if the discovery had been made by a wily old cave grandpa who’d been caving in the area since the seventies, or a dashing young hero out of a local university club. Whoever had made the find was keeping it to himself or herself. ‘In the north’ was the only thing that had leaked out. In Gareth’s view, that had to mean the maze of tight-ish passages known as The Bureaucracy, the same maze we were currently confused in.

Some people knew something. Some pretended they knew something. Some pretended they knew nothing. Some claimed they didn’t know and didn’t care and what was the rush anyway, if there was a discovery everybody would get to hear about it in due time, once the pioneer or pioneers had explored the virgin passages, named them, maybe surveyed them a little. That was the way it was done. You find it, you explore it, you get to claim a tiny slice of immortality. Among cavers that is, because surface dwellers wouldn’t really give a damn. A muddy hole a hundred metres beneath that meadow goes on a bit longer than previously thought, contains more rock, more mud, more darkness. Not even worth small talk in the pub, really. Not unless you were one of the people actually going down there to actually see it, to do it.

Gareth took the passage that had a slight upward slant. I guessed it was heading northeast, maybe. I had a compass, but the nature of The Bureaucracy is to mess them up. There’s a vein of iron buried in the rock around here, somewhere, too deep for anyone to dig up but just big enough to make compasses a little bit untrustworthy. I knew that and I was pretty sure Gareth had to know it too. At least he was not looking at his compass at all. He was just following his nose. Even though this was an unfamiliar section of cave to him, he claimed he understood how the entirety of Dwyn Gwaedlyd flowed. Gareth had a feel of the place, he had studied its formation, seen how the faults had set, what strata of rock lay where, how water, air and stone had moved, were still moving. In other words, he had a gut feeling.

I was beginning to think it was bollocks.

The Bureaucracy (the “The” is always capitalised, even when speaking) kept twisting and turning and giving us the runaround like a, well, a bureaucracy. Truly somebody in the late nineties or whenever this particular bit of inside-out spaghetti had been discovered had had a really witty day. The place was dry, awkward, seemingly endless and devoid of character. All the passages looked like all the other passages. It wasn’t difficult going by any means, merely mind-numbingly samey, rounded narrow limestone tunnel covered in dry, pale brown mud. Most of the time a taller person would only barely be able to walk upright here. Every now and then he would need to crouch to get through a lower spot, or turn sideways to fit through a tighter section. At times you had to get on your hands and knees and crawl, sometimes you even needed to go flat-out on your belly. There were occasional holes leading up or down, some of which were useless dead ends and others took you into another mud-caked narrow passage that looked exactly like the one you’d just come from. The twisting meander had no echo, and it swallowed all sounds pretty fast. Not that The Bureaucracy had any ambient sounds to speak of: there was neither water nor draught to make any noise. Mostly you just heard what the person right in front of you or behind you was saying or doing. There were hardly any bigger chambers, you traveled in a single file, and if you wanted to bypass someone, you did it at a junction. After thirty minutes most visitors have just about had their fill of the place, and start longing for bigger chambers, impressive decorations, deep open pits or beautiful underground streams.

We’d been here for something like three hours, which might have been the longest time anyone who wasn’t doing a survey had spent in the place on purpose. During all that time there had not been a single reason to take out my camera, except maybe if I had wanted snaps of what was quickly turning into one of the dullest, most pointless underground forays ever. Briefly I also wondered if we really were lost, or badly confused, and what we would do if this was the case. I knew that I hadn’t had a clue of our position in more than an hour. We had gone forwards and backwards, seen the same junctions from several different directions, or places that looked deceptively like the same junctions but considering that everything in The Bureaucracy looked the same, might have been different ones. I wasn’t really concerned yet, but the slightest of worries had begun to settle in the pit of my stomach. The Cave Rescue callout counter in the clubhouse was still standing at zero for this year, and nobody really wanted to be in the first party to break the streak.

Yesterday evening at the pub Gareth had convinced all of us that this was a good idea. Somewhere in the far north something new and marvelous was waiting, and Gareth was certain he’d guessed where to look for it, and that we only needed to take the trip into that general section of the cave in order to stumble across it. After three pints it had felt like the most reasonable thing in the world. And, as much as it shamed me to admit it, I’d still have liked the plan, if it had a chance in hell of actually working. This morning when a slightly hung over yours truly woke up to Gareth ringing her up she was starting to have second thoughts. But you really couldn’t say no to Gareth.

… okay, so that part’s not strictly true. I could easily have said no. If I had said anything except “be down in a minute” when he rung me, I’d have been simply left behind. Gareth had been impatient to take off, and I was hardly the only cave photographer around. Hell, even Gareth himself probably knew how to use a camera, even if he had no extra flashguns and no idea of picture composition. But taking stills is easy if you don’t care about quality, and Gareth just wanted someone to document what the party would inevitably find. I wanted that to be me, for a load of complicated reasons. I had no idea what exactly had convinced the others to spend their first day of a bank holiday weekend on this particular trip.

The passage was becoming more narrow, and the ceiling was getting lower. Gareth turned sideways, and I did likewise. It was easier for him, since he’s this tall sinewy type, whereas I am small but, um, well-proportioned. I was wiggling and trying to avoid getting jammed by my boobs. Behind me Joy was having no difficulties, what with her athletic climber’s body and all. I caught the look on her face though, and figured she wasn’t really happy about the way this expedition was going. I didn’t know her that well, but she’d never really struck me as the calm and patient type. If this was going to turn into an eight-hour adventure in The Bureaucracy, Gareth was going to get an earful, and not from me. I just wished I wasn’t stuck between him and Joy when it happened. Actually I didn’t want to be anywhere near either at the time.

The passage made a sharp turn, and then narrowed to almost nothing, the ceiling dipping down as well. A dead end. We’d seen plenty of those already, but the disappointment is always just as fresh.

“So, another wrong way?” I said.

“Nope”, Gareth replied, even though he stopped to look around. He didn’t really have room to turn his head. I had to admire his confidence, even though it was starting to feel more and more like applied stupidity. Behind me Joy drew a heavy breath. I didn’t feel like hearing what she might want to say.

“What makes you think that then?” I asked before Joy was able to get a word out.

“There’s a draught here. I can definitely feel it. Be quiet for a bit, Nasha, and everyone else as well.“

We hushed, even though there wasn’t much point. I couldn’t feel anything really. If the air was moving, Gareth was between me and the vent. I couldn’t hear anything either.

No, wait. I could. There was the faintest echo of a drip. But there wasn’t supposed to be any water here. There hadn’t been any running through The Bureaucracy for thousands of years. We certainly hadn’t seen any coming here. The air in these passages was dry and dusty, and three hours of breathing it left your nostrils caked in dust, your mouth and throat dry. Was it just my imagination, or was there now the slightest hint of moisture on my tongue?

Gareth removed his white, mud-caked helmet, so as to be better able to turn his head. He sniffed around, then he pressed onwards, crouching down. The fissure became really narrow as the bumpy ceiling came down to meet the floor. Gareth stuck out his neck beyond the bump, and looked up. I could practically hear his grin spreading from ear to ear.

“There’s a way on up here”, he announced.

3

Gareth turned his head to look at us. His grin was just as wide as expected.

“Does it really go? You’re not just taking the piss?” Tully’s voice said from behind Joy. Gareth nodded enthusiastically. “I feel a draught, and I’m pretty sure I hear an echo. It certainly doesn’t look like anything The Bureaucracy is supposed to have. I’m going up to have a look. It’s a bit tight, but I think we’ll manage.”

He put his helmet back on and started to wriggle into an awkward position that would enable his climb up the smooth muddy walls. There were no apparent handholds or footholds. Of course that never stopped anyone, or him anyway.

“Need a boost?” I asked.

“Nah, I’m good.” He raised his hands up, sort of grabbed or squeezed something, pulled himself up a bit, then slid back down. This repeated four or five times.

“Can you let me try?” Joy asked. Her tone was irritated. She would be the sensible choice for the job. Joy was by far the smallest of us, and unlike Gareth’s, her oversuit wasn’t made of slippery yellow PVC but greenish-blue Cordura that offered way better friction against the dry mud. In addition, Joy was a superb climber. Not only a cave climber but an actual climby climber who’d scale featureless rock walls for sport. I’d seen her on the limestone cliffs on club picnics. Somehow she found something to hold on to in any surface. Of course, as Gareth would point out, rock climbing skills do not automatically translate into cave climbing, but nevertheless Joy was really impressive at getting up things.

“I’m already doing it”, Gareth replied.

“Well you’re not getting anywhere.”

“I’ve only just started. Give me a minute.”

“You’re making no progress.”

“You couldn’t fit past Nasha anyway.” This was very true. The passage was tight even for one, and if we wanted to swap places, we’d have to back up all the way to the junction, all five of us. Gareth and Joy might just barely be able to squeeze past each other here, being that they were both really slim but I didn’t have a chance.

Caving teaches you a lot about body image. Mine is as confused as anybody’s I guess. On the one hand, ever since I was a teenager I’ve had big boobs, and all the social advantages that come with them; back in uni I found it easy to get guys to pay attention to me and buy me drinks just by wearing a shirt with a low neckline, whereas girls shaped like Joy were too boyish to be noticed. On the other hand, I have always needed to watch what I eat unless I want to balloon into a proper beached whale, and even when I’m being really careful I seem to be constantly putting on weight. Joy can eat whatever she pleases, and consequently does. I think she lives on chocolate. She has a perfect body for athletics, which is the kind of body every woman is supposed to wish they had.

Even if my heaviness didn’t keep me from doing any sports at all, I always did feel kind of inferior and envious of the Joy-shaped people who seemed to be made for them. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be as physically active as them, it just was more difficult for me. Sometimes I managed to convince myself that it didn’t matter, at other times I succumbed to the counterargument that it did matter, that I was a horrible fat pig and a failure as a human being, etcetera etcetera, insert standard body image issues created by the advertising and entertainment industries here.

Caving changed that for me. Here was a physical activity that seemed to actually embody the idea that everybody is beautiful and useful in their own way. Caving is very physical, hell, as an activity it’s supposed to burn about as many calories as triathlon, but all the good triathletes you see have the same basic body type. Not so for cavers. Tall and long-limbed? You’ll do fine in climbs and traversing across chasms, but beware of tight chimneys, and sharp turns in crawls or chokes — your long bones will be a hindrance. Small and slim? Crawls and squeezes are going to be easy, but be mindful when crossing chasms, going up or down larger chimneys or traversing – your limbs might just not be long enough. Short and stocky? You might get stuck in a crawl from time to time and probably won’t be that great at scaling walls, but many chimneys will be easy, you’re likely to go far on just a single meal, will do fine in wet sections and probably won’t get very cold. Large and wide? You have bit of the short end of the stick in everything related to squeezing, but you will do well in everything requiring reach and probably not get as cold as the slim ones. Also, people will want you on their trips as a pack mule.

Everything is a trade-off. There’s no such thing as the perfect body type for caving. Realising that even my shape and build had actual, discrete physical advantages here was one of the reasons I felt right at home underground.

Looking at where Gareth was trying to fit in made think this might be one of the times my fat arse was going to be a hindrance instead of an asset, although you never can be sure by just looking. I couldn’t exactly see the chimney he was attempting to conquer, but it didn’t look particularly big. Since I already seemed to be in the middle of his and Joy’s burgeoning argument, I decided to take bold, decisive action. I wriggled forwards toward him, grabbed the bottom of his thrashing wellie, and steadied it, giving him a foothold in the process. “Go on, up with you”, I told him.

Gareth didn’t protest. He put his weight in my hands, pushed up, grabbed something but didn’t quite manage to hold on, and started to slide down again. I was quickly under him, and he stepped on my shoulder. I might have collapsed under his weight, but the tight end of the passage offered good bracing and kept me upright. There wasn’t really anywhere to collapse to.

For a few seconds Gareth’s 80 kilos pressed down on me. Then he managed to squeeze himself somewhere and started to chimney on up. I chanced a look upwards. There was a proper vertical tube going up with a bit of a twist at the start: the first bit looked tight, but after that it seemed to get wider. I moved back from under it, in case Gareth slipped and fell down.

He didn’t, though. The skish-skish sound of PVC sliding on rock went on for a couple of minutes. Down in The Bureaucracy Joy was wearing an expression somewhere between irritation and excitement. I took out my camera and snapped a shot of Gareth’s bum going up the chimney. Most unstaged action shots in a cave tend to prominently feature the arse of the person in front of you. Gareth’s was nice and fit, even though the yellow PVC wasn’t particularly flattering. For good measure I also snapped a pic of Joy and her impatient face. Or tried to, anyway, since the flashgun hanging from my belt wouldn’t fire. I swore at it colourfully.

“Maybe you should actually teach yourself to use that thing one of these days”, Tully said. He had sneaked into the frame and tried to photobomb the picture by mimicking the expression he knew Joy would be wearing. It might have been funny if it hadn’t been what he always did.

“Get out of my picture, Tully”, I told him. Joy realised what he’d been doing and elbowed him in the ribs. Farther back, Eaton, the last member of our party, was invisible behind the corner, and quiet as usual, which suited me just fine.

The sounds from the chimney stopped. Then Gareth called out. His voice was excited.

“We’ve found it!”

“What is it exactly that we’ve found?” I called back.

“Get up here and see for yourself. It’s not a particularly bad climb.”

I sneaked a look at Joy. She was looking like she’d explode if she had to wait down here another second. The cave had been here for thousands of years, but she seemed to be anxious it was going to disappear any second now and she had to go check it out right away. At least she was no longer looking angry.

“Want to go next?” I asked, unnecessarily. Of course she did. I started moving backwards, away from the narrow end of the passage. The entire team retreated. Right at the corner, as soon as I got the tiniest amount of space around myself, Joy wedged herself into the opening, apparently determined to pass me in an amoeba-like fashion. “Oi! Ow! Personal space!” I yelped.

“Sorry, babe.” Joy flashed me a smile and pushed the air out of my lungs while squeezing by. For a second I was sure there was no way she was going to fit anywhere, then I was certain than we’d just end up stuck in the passage together, and then she had somehow passed me and was zipping around the corner. When I followed her I could just see her expensive hiking boots disappear up the chimney. Tully rolled his eyes.

As expected, Joy went up the chute in a flash. I positioned myself at the bottom. The chimney looked tight and a bit high for my 160 centimetres, with nothing on the walls offering purchase. After a couple of futile attempts to wedge myself up Tully pushed to the fore and gave me a boost to get me started, even though he looked like a martyr doing it.

Navigating the awkward opening was a bitch. Solid rock does not budge, but fortunately most of my volume compresses when necessary, and by lifting my hands up, breathing out and stomping on my fellow caver I got through surprisingly easy. Wide shoulders would have been more of a problem here. Then I was in the actual chimney with my back pressed against one wall and my knees against the other. It was tightish and didn’t have anything resembling handholds, but my legs were of pretty optimal length for climbing it. Gareth was probably a bit too tall for this bit, and had to use his arms and shoulders instead of his legs. Me, I pushed with my knees, inched my body higher, moved one leg up at a time while keeping myself wedged in place with the other.

The stone was smooth and curvy, all rough edges and sharp corners worn off thousands of years ago. It was cool to my touch. The feeling of being enclosed in a small tube of limestone is unlike anything else in the world — in itself neither pleasant nor unpleasant, just unique. The rock surrounding you will not move, will not bend or accommodate itself to you in any way. You need to be the one to adjust; you need to stretch, flex, compress, breathe out, and if something just doesn’t work, there’s no amount of force that will change the situation. You cannot bargain with the rock and if you engage it in a contest of brute force, you will lose. So you just need to accept that the rock is there and then find the right way to get around it, with forethought and flexibility, not with brute strength.

Some people get claustrophobic in these kinds of places, and although I kind of understand where they’re coming from, I never have. The rock may not move when you push it, but neither will it try to crush you or crumble on you. The only trouble you can get into with solid rock all around you is the one you bring on yourself.

There was caked mud still covering the dark limestone, which was good for friction. Obviously hardly anyone ever came here, otherwise the mud would have been rubbed away and the smooth limestone beneath would have been exposed – and the climb would have had way less friction and been more difficult. A rope might be a good idea, especially since the chimney seemed to be on the high side.

Jammed in the vertical tube I felt the draught clearly. Joy and Gareth weren’t exactly being quiet up there either. Their voices were excited, and judging by the echo there was quite a bit of space at the top. I didn’t really pay attention to what they were saying, since the chimney really was a bit high for my peace of mind. Two metres is routine, four metres I can handle but six metres of nothing except wedging yourself against muddy stone is not really in my comfort zone. Tully was coming up after me, so if I slipped I’d at least have him to cushion my fall.

The chimney widened and started to turn sideways, from a drop into a slide. It would have become a real challenge, except that I spied an actual foothold, then something like a handhold, and then Joy and Gareth, who were sitting in a small space some two metres away and talking animatedly. The draught could easily be felt now, and there was a sound of falling water, not a huge amount of it but not just any tiny drip. There wasn’t really that much room here either, nor was there anything resembling a proper floor, just a metre-and-a-half wide steep slide that turned into the chimney. The foothold I was sort of standing on was practically the only secure place I could see. Beyond Joy and Gareth there was open space.

Gareth turned to me, his face shining. “Nasha, get up here to take some pictures! We’re talking the discovery of the decade!” I still didn’t see any reliable handholds, and just crawling up the forty-five degree slide with a six-metre drop right behind me wasn’t too appealing. Gareth leaned back and offered his hand to me. I managed to grasp it without losing my balance. With little effort he pulled me towards the ledge. I hopped onto the slope, found some uncertain footholds, and scampered up. Joy moved a bit to make room for me between them.

The top of the slope was a round window in the side of a really big vertical shaft. Its walls were dark and wet and smooth, over five metres away from each other, and from the top a steady drizzle of water fell into the abyss below. Gareth’s light was just strong enough to see the bottom, at least thirty metres below us. Or a bottom anyway – it looked like the shaft might continue after a small ledge. We were sitting in the window, our legs dangling over the edge.

I couldn’t see bolts or spits in any of the walls. Nothing like this was mentioned in the survey. Nobody had been down this shaft before. It was unnamed, unexplored, unknown. It really was the discovery of the decade. I took out my camera, positioned the flashgun hanging from my belt, and proceeded to capture the rift, the waterfall, the chimney and the triumphant expressions on everybody’s faces to the best of my ability.

4

After that we had to head back out.

The chasm that we’d found absolutely required further investigation, but we had no means of doing so. We were going to need lots of rope and connectors, SRT kits for everyone, as well as a hammer or a drill and some bolting tools. There were no good natural anchors to hang ropes from, the shaft walls were all smooth and featureless. So after everybody had chimneyed up to the window and gawked at the big rift and I’d taken everyone’s picture with everyone and Joy had taken one of me with the blokes, there was nothing to do but to slip back into The Bureaucracy and start trekking towards the exit.

I wished we could have left a rope in the chimney, because climbing it unassisted was never going to become one of my favourite activities. We even had a short handline in one of the tacklebags and we could have tied it around the small protrusion at the top we had used as a handhold. However the others were adamantly against it. I suppose Gareth was dreading the idea that someone else might use it and get up our chimney, or that somebody else as much as discovered the place before we had a chance to return to it. So, no rope, not this time anyway.

The Bureaucracy was easier on the way back, as is often the case. Whether we had been lost, confused or just slow earlier, we got out of it in an hour with hardly any route-finding problems. Eaton took the lead on the return trip, and he didn’t seem to have any hesitation in finding the right turn or opening. After the meanders it was nice walking passage, a boulder choke, a bit of wading in the streamway and finally the wet crawl up to North Entrance. The dry weather meant that only a small stream was coming in through the low slot of an entrance; in heavy rain, the crawl could flood completely. The trip had taken only six hours out of the projected ten, so nobody had any reason to worry. Outside it was a warm if a bit cloudy August afternoon and a kilometre walk through a hillside full of bleating sheep to the car park. There were a couple of other cars, belonging to other cavers that had gone down the North Entrance and were undoubtedly having a scenic trip in the streamway.

We changed out of muddy kit right there, stuffed it into oversized bin bags, washed our hands and faces a bit. Gareth rang the club to report that we’d come out safely and that our trip could be erased from the callout whiteboard. We then climbed into our cars and headed out to the pub. It was pretty crowded, as expected on a Saturday evening. Of the local places we’d selected the one least frequented by cavers, and a quick look inside confirmed we were the only ones around. We managed to take over a table in the corner.

Tully had a copy of the ODG survey in his car. After eating our fill of curry and downing our first pints we spread the survey out on the table. The whole thing didn’t fit, but we were only interested in the northern sections of the streamway, plus everything around The Bureaucracy. I felt like a pirate huddling next to a map showing the way to buried treasure. It wasn’t that far from the truth anyway. However, there wasn’t much to be gained from studying the map of known reaches of Ogof y Dwyn Gwaedlyd. The Bureaucracy was the northernmost end of known exploration, and there was no mention of a big shaft anywhere close to it.

“That’s it then. It really is a whole new discovery, not surveyed”, I declared. The excitement at the idea shone on everybody’s face. I think the only thing keeping us from cheering out loud was the lingering fear that somebody who was into caving would walk right into the pub that very second.

An unexplored section of a cave is a big deal among cavers. It’s like finding a new, undescribed species of a bird for an ornithologist, or discovering an as yet unconquered summit if you’re a mountaineer. There are several reasons for this. There’s the thrill of exploration, the sense of being somewhere nobody has ever been before, of being the real, actual, honest-to-God first person to see or do something. There’s the pleasure of encountering the underground world in a pristine state. Once a place starts getting visitors, even though damaging the cave or littering it is an anathema to every caver, every visit by humans inevitably changes the environment a tiny bit. There are some features underground so incredibly fragile, that once discovered, they will start crumbling and will be totally gone after the first twenty people or so. And of course there’s the immortality to be gained by coming across something huge and interesting, naming it, getting forever remembered as the one who discovered it. The bigger the find, the greater the glory.

“It’s not just any bit of passage”, Gareth said. “I’m reasonably sure this is the Second Series, the system that has been theorised to exist next to the known sections of ODG.”

Tully snorted. “Yeah, sure it is. Why not a tunnel connecting Wales to Ireland while we’re at it? People have been looking for the Second Series for ten years, and no one’s gotten anywhere.” We ignored his pessimism.

“We need a name for the shaft”, Joy chimed.

“Not until we’ve been down it”, Gareth responded.

“There’s no harm in making up a few candidates. I’m thinking About Fucking Time Pitch.”

“The Memory Hole”, I suggested, but nobody caught the reference.

“More like Joy’s Deep Wide Hole” Tully said, and Joy shot him in the arm. Eaton had been eating in silence, but Tully’s suggestion got a chuckle out of him at least.

“No naming anything we haven’t done properly yet”, Gareth declared. “If we absolutely must name something, there’s the chimney.”

“Joy’s Tight Chimney”, Eaton chuckled and adjusted his big glasses. He had been wearing them even down in the cave. I had no idea how he could cave with those things on. He must have been totally blind without them. His voice was a nervous, annoying titter.

“Could be that someone else has already named the chimney though”, Tully said, putting to words something we all were thinking. “Maybe the shaft as well.”

“No one’s been down that shaft”, Gareth insisted. “I checked around the window, and I didn’t see any bolts or drilled holes.”

“Doesn’t mean there couldn’t have been any”, Tully replied.

“It’s not the kind of thing you miss”, Gareth said, meaning the kind of thing I’d miss. Not in a particularily unkind way though. He was convinced enough of his own superiority to not even need to put others in their place. Still, Tully took it as a snub, of course.

“You could go down the shaft without necessarily needing to drill at the top. All you’d need is a sturdy rope and a low belay from the bottom of the chimney. There might have been a natural anchor point for a rebelay a bit farther down.”

“Doubtful”, Gareth said. I found myself agreeing with him. What Tully described was technically possible, but I could see no reason why anyone would want to do something like that. If you need to go down a vertical shaft, and there are no convenient natural rock formations to use as anchor points, you drill a hole into the rock and stick a bolt in it (actually two holes and two bolts, if you’re following the proper procedure and want to be reasonable and safe, not reckless and in a hurry) and make an anchor to hang your rope from. That was the sensible way, and would also make you independent of the need for anyone to belay you.

Tully was about to elaborate on his counterpoint, when Joy suddenly hissed: “Oh shite! Sean’s here!”

Our heads turned. A sixtyish man with a graying, short beard, a work vest and worn pair of jeans had just stepped out of a back room. Judging by the set of tools he was carrying he was here on a work call. We hadn’t seen his yellow Ford van in the car park, but if he was here fixing the roof or whatever, it was probably parked in the back.

In addition to running a roofing business, Sean was our club hut warden, and a caver of some thirty years. He was a practical sort, not overly ambitious, got well along with everyone, and loved to gossip. In normal circumstances I’d have enjoyed running into him and would gladly have had a pint with him. Right now, he was exactly the kind of person we didn’t want to meet. There was no way he wasn’t going to see us in a couple of seconds.

Tully was the fastest to react. He picked up the condiment caddy from atop the survey, causing the paper sheet to immediately roll back up. He swiped it off the table just as Sean nodded to the landlord, turned around, and noticed us. He made his way to our table.

“Well, look who’s here”, he said, smiling. We greeted him back, some mumbling, others with fake enthusiasm. Gareth in particular managed to look like he was just happy to see him.

“You alright, Sean?” Gareth said, apparently figuring that it was best to just act normal.

“Mm, working. Just here to give a quote on some renovations these folks are planning. How about you lot? Been caving or what?”

“Yes.”

“No.”

My affirmation and Joy’s denial came out exactly the same time. Sean raised his eybrows. I couldn’t think of anything intelligent to say to save the situation, but fortunately Gareth was on the case. He didn’t even pause for breath.

“Most of us have. Joy figured it was going to be a boring trip, so she declined to come along. Why don’t you sit down?”

“Maybe for just a bit”, Sean said, pulling up a chair. “The wife’s expecting me back by eight though, and I cannot have another pint or I won’t be fit to drive.”

I stole a glance at Joy. She rolled her eyes at me. Nervous laughter was bubbling in my throat, and I tried to drown it with beer as Sean and Gareth exchanged small talk. At least Sean hadn’t seen the survey. Then again, what would it matter if he had? Cavers have surveys out all the time, nothing extraordinary about that. Still, I felt like a kid who’d been nicking sweets. We should have picked some place far off for our post-trip pint, or at least made sure that nobody in the building was even related to anyone who’d ever shown any interest in going underground before settling down to conspire. We’d just been too excited to be careful.

“So was it?” Sean asked, apparently from me.

“Whut?” I replied.

“The trip. Was it boring?”

I couldn’t think of anything to say, but Tully came to the rescue. “We did The Bureaucracy in ODG. Take a guess.” There wasn’t really a point to try and hide it; our trip destination had been on the whiteboard in the club hut.

Sean chuckled. “The Bureaucracy? What would you go there for?”

“Nasha’d never been there before”, Gareth replied.

“My question stands”, Sean said, smiling even more broadly. The maze had a reputation as a place where nobody wanted to go, unless…

“I wanted photos”, I said before anyone else could say anything. “Got some good ones too. Want to have a look?” I reached into my backpack and took out the camera.

I could pretty much feel everyone around the table freezing, as they saw me preparing to bring out the exact thing we didn’t want anyone to know about. Joy grimaced, Tully’s mouth opened, Gareth’s eyes widened, and even Eaton’s unfocused expression caught a hint of panic. I held my breath.

Sean shook his head. “Nah, I’d rather see them full-size on a big screen some day. Actually, I think I better get going. I’m going to drop by at the club hut on the way. Tessa was going to set up a video call to Adam and the French expedition in the common room, I’ll see if I can catch it. Anyone else coming that way? Give you a lift.”

“Maybe later”, Gareth replied, covering his earlier astonishment with his normal manner like nothing had happened.

“Say hi to Adam for me”, I said.

“Will do. Cheers.” He got up and left.

When the door had shut after him we all sighed and sat back in our chairs.

“Christ on a rope, Nasha”, Tully said, shaking his head. “You going to put the pics of what we found on the internet next?”

“Relax, I know what I’m doing”, I replied. “Sean didn’t have his glasses, and he’s embarrassed to admit he can’t really see that well without them anymore. I was betting he’d rather make his excuses and leave than try to squint at my camera.”

“What if he’d just put them on?”

“I’d have just claimed that the camera seems to be on the fritz. It does that often enough anyway.”

“… Yeah, I can see that. It’s a good thing people are used to you not getting your kit to work.”

“Shut up, Tully”, Joy said, laughing. “Nasha, that was totally awesome! Remind me never to play poker against you. I’d lose my shirt.” She made goo-goo eyes at me.

“That I’d like to see”, Tully said, and Joy gave him the finger. Still, he stopped bitching. Eaton and Gareth were wearing relieved smiles as well.

“So, the secret stays with us, for now”, Gareth said. “That’s all good. We can plan our next move.”

“The shaft?” Eaton asked.

“The shaft”, Gareth affirmed.

“If nobody’s been down it yet, they will, shortly”, Joy said. A small pause. “… If that is the thing that somebody found – but it is, right? It’s got to be.”

Nods all around. “Yes. And even though a big chunk of the club is in Europe right now, there are still people crawling around in the local holes too. We need to move fast in order to be the first”, Gareth said. Nobody had any objections. Even Tully, usually the contrarian, kept silent.

We were, I’m sure all of us knew, being unbelievably hypocritical. This was obviously the discovery someone else had made earlier. It was their find, not ours, and by all caving ethics and codes we should have kept our dirty mitts off it, and left it alone for them to explore in their own good time. It would have been the honourable thing to do; it was also something that we obviously had no intention whatsoever of doing. I’m not going to sugarcoat it: we were going to steal someone else’s discovery just because we could, and despite everyone of us (or most of us) maybe having some misgivings about this, it was not going to stop us.

People like us are why you cannot have nice things, why you keep your dig sites and exciting leads to yourself and do not talk about them where others might be listening. There’s always some arsehole willing to let you do all the hard work but more than ready to jump in once the fun bit starts. I had yet to celebrate the first anniversary of my caving hobby, and already I was becoming one of the bastards. I could have argued that if they really had wanted to keep us out they should have been official about it, declared that bit of The Bureaucracy an exploration site and respectfully requested that nobody go there until it had been properly investigated. Now all we were doing was some regular caving, and when we found an unexplored passage, why, we’d do what any normal caver would do: check it out to see if it goes. Their own fault for not marking the spot with an “Exploration site for Charlie Caver & Co, all others go away!” sign.

If they had done that, I figured it would probably have deterred our team, since Gareth would have found it beneath him to just ask us all to ignore it. Instead it would have attracted the other kind of opportunistic bad guys, who’d have read the signposts and then followed them until they found something unexplored. It was a lose-lose situation for the original discoverers. The only way they could have gotten away with this was if they’d kept their mouths shut and not even hinted that a recent expedition had produced something fascinating. They hadn’t, somebody had been babbling after a pint too many, and they would have to pay for it. In glory, if not in cash.